|

Issue 21 December 2009 |

| Off-Gassing... | |

| (Web Version) |

Merry Christmas

and a Happy New Year to everyone.

| The AGM |

|

A slide show was organized this year by Phil Kinsman, illustrating the

varied activities that the club gets up to on its trips away. There has

been a general change around in the committee members, which now reads

as follows:

|

| Review of the dinner dance |

|

For those of you unable to attend the Dinner Dance, (really good excuses

for failing to turn up could be published in the next newsletter,

otherwise itís beer fines) or the AGM, here is a summary of awards given

and what your new committee will look like Ė no photos, itís just not

pretty. New sports divers are: Ashley Munday Paul Lathbury Stacey Carless Adrian Meek Andy Smith Charles Swannie The Beresford Award, given by the committee, went to Chris Bennett. Trainee of the Year went to Stacey Carless DOís Award went to Paul Lathbury Members Member went to Chris Bennett Dive Monster was won by Paul Lathbury The Brass Ass went to Sue Astle Ė whose accident with a bikini bottom made this a very apt award. A good time was had by all, but obviously the beer enthusiasts were holding back as there was still some left at the end of the night (beer, that is). Is this the worrying trend of a keep fit drive, or the after affects of swine flu? Thanks to Lil as always for organizing the event, and presenting the Beresford Bowl. Thank you as well to everyone who supports this event year in and year out, and those new members who came along. It is important to the committee and the club that we get together to celebrate being members of one of the best clubs in the country, which is after all, down to the busy workings behind the scenes and the members themselves. |

| Wreck of the Month - HMS Scylla |

|

50 19.64N 03 15.20W Itís been 5 years since the Scylla was sunk off Plymouth, becoming Europeís first artificial reef. This is a brief update about how successful it has been, but first, the history. Her pennant number was F71. She was launched from Devonport Dockyard on 8 August, 1968, 2500 tons of broad-beam Leander-class frigate and the the fourth warship to be christened HMS Scylla since 1809. On 14 February 1970 she joined the Western Fleet in the Med with her 263 crew, reaching her top speed of 28 knots from her 30,000hp geared-turbine engines in trials near Gibraltar. She carried Seacat missiles, a Lynx helicopter and 4.5in guns. In 1971 she joined the Far East Fleet in Australia, Japan, Singapore and Hong Kong and then the Beria Patrol, returning to Plymouth in February 1972. In January 1973 she collided with the Torpoint-Devonport ferry in fog. No one was injured but her captain was court-martialled and found negligent.  Playing

bumper cars with Icelandic fisheries vessels in the Cod War of

1972-1976, Scylla earned a reputation as the toughest RN fishery

protection warship. In June 1973 she was accused of helping two British

trawlers to ram the Icelandic gunboat Arhakur. Scylla claimed merely to

have stood by. Six days later, however, she did take positive action

after being rammed by the gunboat Aegir. She rammed much harder back and

the gunboat limped away. Playing

bumper cars with Icelandic fisheries vessels in the Cod War of

1972-1976, Scylla earned a reputation as the toughest RN fishery

protection warship. In June 1973 she was accused of helping two British

trawlers to ram the Icelandic gunboat Arhakur. Scylla claimed merely to

have stood by. Six days later, however, she did take positive action

after being rammed by the gunboat Aegir. She rammed much harder back and

the gunboat limped away.Scylla later seemed to be everywhere - entertaining US President Jimmy Carter aboard off the Leeward Islands, in the Channel to scatter the ashes of Cruel Sea author Nicholas Montserrat and, in 1980, helping the victims of Hurricane Allen in the Cayman islands. In 1986 she was on Gulf Patrol duty and in 1992 was given the freedom of Aberdeen. December 1993 saw Scylla paid off. And on 27 March 2004, the 372ft frigate, with a beam of 43ft and drawing 19ft, was 'placed' on the seabed in 21m in Whitsand Bay - not far from Devonport. Marine scientists believe the scuttled former Royal Navy frigate is now home to about 260 sea species, surpassing expectations both in terms of visitors and in colonisation. While Scylla has attracted many of the typical sea creatures associated with a shipwreck, such as conger eels, whiting, mussels and barnacles, queen scallops, cuttlefish and scorpion fish, there has also been some other visitors, including a nationally rare sea slug and pink sea fans, which colonised in August 2007. It appears that all round, the wreck has become a great success. It is believed that it has generated up to £30million in its first five years, which has created a massive boost to Plymouthís economy. Numerous business leaders in the South West region doubted the  National Marine Aquarium-led project, believing it would fail, but

figures show about 42,000 people have visited the wreck on 7,000 dive

boats since its spectacular sinking on March 27, 2004.

National Marine Aquarium-led project, believing it would fail, but

figures show about 42,000 people have visited the wreck on 7,000 dive

boats since its spectacular sinking on March 27, 2004.The National Marine Aquarium has been monitoring and logging the wreck for the last five years and will continue to do so for a further five. |

| Creature of the Month - Vampire Squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis) |

|

|

|

Thank you to everyone for their contributions and comments and if you have anything that you would like to add to the newsletter, let us know by 20th January so it can be included in the next issue. |

Hope you enjoyed this issue. Coming up in the next issue ó highlights of coming year. |

|

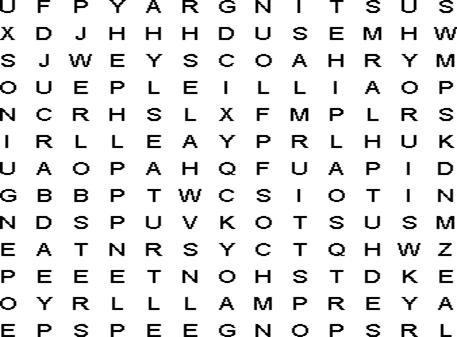

Sea Creatures

Find and circle all

of the sea creatures that are hidden in the grid.

Crab

Penguin

Stingray

|

|

Thanks to the Editors: Lin Noakes, Wendy Munday, Phillipa Cresswell,

![]()