|

Issue 20 November 2009 |

| Off-Gassing... | |

| (Web Version) |

Thanks to everyone who attended the Dinner Dance

an excellent night out , as usual.

| Plymouth - RIB Vs Hard Boat |

|

So, what are the best type of trips to go on?

Is it a rib dive, where you are in total control of where you go

and what you do, or a hard boat, where the skipper is responsible for

getting you to a good dive site?

Having had the opportunity of doing both trips within a week of

each other, I thought this would be an ideal way of looking at the pros

and cons.

First of all, the rib. There

has been a lot of discussion in the club about whether to keep the rib,

replace it, or just not bother with a boat at all.

If you are willing to spend a little time in preparation, the rib

is great for a do-it –yourself weekend.

You decide what you want to do, when and how, with the added

bonus of driving it around and having the time of your life doing it.

Yes, you have to allow yourselves more time to get it launched,

but as long as you follow the basic rules of boat handling and have

someone with some experience with you, there is a sense of achievement.

The rib allows about 6 divers comfortably.

It is up to the group whether you just a designated cox, or a

diver/cox. A lot of people

enjoy the freedom of coxing the rib and organising the challenge of

picking up divers. That is

also interesting. Getting

back on the rib isn’t difficult, but its not graceful.

As long as everyone helps out, there is no problem. Next, the hard boat weekend.

Basically, you turn up with kit at the specified time, and your skipper will do

his utmost to take you to a decent dive site.

You are out all day, which means sometimes that things can get unpleasant

if seas are rough, but generally it is a relaxing way of diving and with twice

as many people as you would get on the rib.

So, two totally different ways of diving at sea that we, as a club, are lucky

enough to have the opportunity of experiencing.

The rib weekend worked out about half the price of the hard boat which is

a consideration, but the group needs access to a vehicle capable of towing,

launching and retrieving the rib.

Both have pros and cons and are really totally different weekends away, but

knock either until you have tried it.

So, next time you hear about a rib trip, sign up for it, as it’s fun and

satisfying in a number of ways. The

same goes for hard boat weekends - always a laugh and the

chance of trying something different to a quarry can’t be bad!

Remember also, both types of diving always have the fall-back option of

the pub if everything doesn’t go to plan and the weather is inclement.

All in all, everyone’s a winner.

|

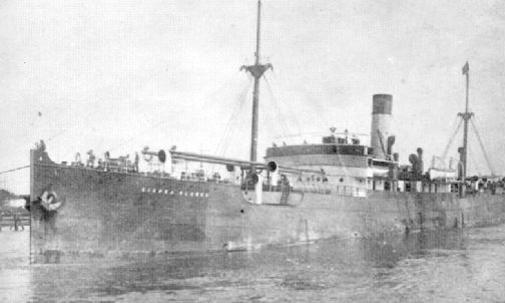

| Wreck of the Month - The Maine |

| Lat / Long : 50 ° 12 ' 45 '' North - 3 ° 50' 53''

West

The Maine came to a sticky end

on a misty day in March 1917, when a torpedo from a lurking U. boat hit

her in the port side, round about her number two hold when she was about

ten miles off Bolt Head. The Maine, a 3600-ton cargo ship, was loaded

with horsehair, goatskins, and five hundred tons of chalk, outward bound

from London to Philadelphia. Very soon the holds started to fill up and

Captain Johnson, after sending off distress signals, set course for the

nearest land in a vain attempt to beach her. The crew of forty-three must

have been terrified that the U. boat would finish them off, but for some

reason the U. boat never pressed home his attack. He was either very

confident or just lost the Maine in the mist. In any event it did not

really matter because that one torpedo was going to be enough to sink

the Maine. As the miles drifted slowly by the Maine became more and more

sluggish until the water level rose high enough to drown out the

engines. As the Captain ordered the lifeboats swung down and prepared to

abandon ship, the Royal Navy torpedo boat appeared out of the mist and

soon took off most of the crew. Because Hope Cove was by now so close,

the Captain of the torpedo boat offered to try and tow the stricken

steamer to safety. However, by now the Maine was almost half full of

water and the towropes kept parting under the terrible strain. After a

while the main bulkheads collapsed, and the Maine sank slowly and

gracefully to the bottom about two miles off Bolt Head. Nowadays the wreck lies upright

on a bed of fine shale and sand in approximately 30-35m of water, with

its bows towards the shore across a strong current. |

| Creature of the Month - Urchins |

|

Sea urchins or urchins (Aristotle’s Lanterns) are small, spiny, globular

animals that compose part of class Echinoidea. They are found in oceans

all over the world. Their shell, or "test", is round and spiny,

typically from 3 to 10 cm across. Common colors include black and dull

shades of green, olive, brown, purple, and red. They move slowly,

feeding mostly on algae, but can also feed on a wide range of

invertebrates such as mussels, sponges, brittle stars and crinoids. Sea

otters, wolf eels, and other predators feed on urchins. Left unchecked,

urchins will devastate their environment, creating what biologists call

an urchin barren, devoid of macroalgae and associated fauna. Where sea

otters have been re-introduced into British Columbia, the health of the

coastal ecosystem has improved dramatically. Sea urchins are also

harvested by humans and their roe is served as a delicacy.

…the urchin has what we mainly call its head and mouth down below and a

place for the issue of the residuum up above. The urchin has, also, five

hollow teeth inside, and in the middle of these teeth a fleshy substance

serving the office of a tongue. Next to this comes the esophagus, and

then the stomach, divided into five parts, and filled with excretion,

all the five parts uniting at the anal vent, where the shell is

perforated for an outlet... In reality the mouth-apparatus of the urchin

is continuous from one end to the other, but to outward appearance it is

not so, but looks like a horn lantern with the panes of horn left out.

|

|

Thank you to everyone for their contributions and comments and if you have anything that you would like add anything to the newsletter, let us know by 20th December so it can be included in the next issue. |

Coming up in the next issue — review of the Dinner Dance and AGM, news of the new committee and highlights of coming year. |

Thanks to the Editors: Lin Noakes, Wendy Munday, Phillipa Cresswell,

![]()